- Home

- Watson, Sterling

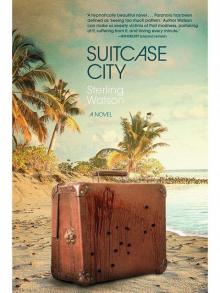

Suitcase City

Suitcase City Read online

Table of Contents

___________________

Part One

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

Part Two

NINETEEN

TWENTY

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

THIRTY-TWO

THIRTY-THREE

THIRTY-FOUR

Part Three

THIRTY-FIVE

THIRTY-SIX

THIRTY-SEVEN

THIRTY-EIGHT

THIRTY-NINE

FORTY

FORTY-ONE

FORTY-TWO

FORTY-THREE

FORTY-FOUR

FORTY-FIVE

FORTY-SIX

FORTY-SEVEN

E-Book Extra: excerpt from Fighting in the Shade

About Sterling Watson

Copyright & Credits

About Akashic Books

To Mike, the best brother a guy could ever have

Acknowledgments

My thanks to Jamie Gill for library research, to Judd McKean and Suzy Johnson for help with boats, and to Tom DiSalvo and Margarita Lezcano for correcting Spanish. I am indebted to Margot Hill, Dean Jollay, Bill Kelly, Dennis Lehane, Ann McArdle, Peter Meinke, Bill Miles, and Jay Nicorvo for criticism and commentary. Your insights made this book better. Thanks to Jerry Witucki for one very good line. Thanks again to the marvelous crew at Akashic Books, especially Ibrahim Ahmad, who guided me through some difficult revisions with patience, good humor, and keen intelligence. And, as always, a loving thank you to Kathy, the best reader of all.

Lay your sleeping head, my love,

Human on my faithless arm . . .

—“Lullaby,” W.H. Auden

PART ONE

ONE

1978, Cedar Key, Florida

Jimmy Teach left professional football at the age of twenty-four, and his life went into a fast fall. He squandered money on bad friends and foolish business deals and the drink and drugs that went with them. He lived hard and the months passed and it became a slow suicide. He woke up one morning in a car he didn’t own in the driveway of a fashionable house in Atlanta with a policeman at his window. Teach had no idea who owned the house or why he had come to it. He had passed out with the engine running. A half-open window and an empty fuel tank had probably saved him from a blue-lipped death.

Teach went home broke to Cedar Key, Florida. To start over in the old place. To remember who he had been, build a man again. One he could stand to be. People in the little towns were used to their sons and daughters coming home. The little places sent out a strong call to their own. The call was, Come back. Come back and be small again. And many did.

Teach looked for jobs in the local fishery, but the crabbing, oystering, and gillnetting had fallen on hard times. He worked in kitchens, then as a bartender. At first it was hard because people asked questions. As simple as: what are you doing back here? As difficult as: what happened to all that football money? But it wasn’t long before Teach was one of them again. Before he was nothing special.

One night, Teach was serving a party of sun bunnies who had arrived on a big motor sailer. He was dropping the paper umbrella into a banana daiquiri when a black man said, “Hey, what you doing back here?” The question was old, the man was vaguely familiar.

The man looked over at the people he was with. They were the easy, pretty people who stopped in at the Cedar Key docks and ate in the restaurants and then sailed on to the next piña colada or planter’s punch. Teach called them the Whatever People. Whatever was an attitude, a place where people had enough time and money to let things happen to them, things that felt good. Teach said, “Do I know you?”

“Hey, Jimmy, come on.” The man’s accent was local, the black version of it anyway, but the attitude was from Whatever. Teach still couldn’t place him. The guy laughed, leaned close, and said, “Delia B., man. Remember?”

It all came back. The Delia B. was a trawler Teach had piloted when he was fifteen years old. An accomplished kid with a boat, he had coasted the Delia B. into a secluded canal bank where she would meet a rented truck. When her cargo was off-loaded, he would take her back out again, jump into a skiff tied to her stern, and wave goodbye to his friends who would clean her out and run her back around through Key Largo and up to Homestead. The black man’s name was Bloodworth Naylor. Nine years ago they had been business associates.

“Naylor,” Teach said, “how you doing, man? It’s been a long time.”

Teach remembered it all now, the nights he’d brought the boat in, the fat envelopes of cash, the things he’d bought for his widowed mother, the secrets. Bloodworth Naylor glanced over at the Whatever People, lowered his voice. “Ah, you know. I get along one way and another. Right now I’m babysitting tourists for ten bucks an hour.”

After Teach closed up that night, he let Naylor in the back door and they sat in the dark bar. Naylor was crewing on the motor sailer, running tourists up and down the coast for a couple of New Age gurus who had them meditating in string bikinis and Speedos and contemplating the Tao. “Bunch of mantra-mumbling fools,” Naylor said over his third rum and lime. He stared at Teach. “You probably think it’s a coincidence us running into each other like this.”

Teach raised his Wild Turkey and sipped. He was supposed to smile, say yeah, he thought it was a coincidence. He glanced around the bar. A table of waitresses over in the corner counting tips and telling evil-tourist stories. The cleanup crew coming on with mops and buckets. This was Teach’s life after football. Apparently, the man he had come home to build was a bartender. Bartenders know the past always comes looking for you.

Teach said, “You’re doing it again, Naylor. You’re back in the import business.”

Blood Naylor smiled. “Not yet, but I’m thinking about it. Now that you’re back in town.”

* * *

The trawlers didn’t come from Homestead anymore, and they didn’t cross to Freeport for the product. Teach and Bloodworth Naylor were subcontractors for a consortium of Guatemalan importers. The Guatemalans owned a mother ship designed to transport yachts across the world. Its huge bow doors opened, boats were floated aboard and secured, then the seawater was pumped out. They brought the mother ship up the Florida coast at night, floated an eighty-ton shrimper named the Santa Maria out of her bow, and three Guatemalans named Julio, Carlos, and Esteban piloted the shrimper inside the twenty-mile limit. The shrimper’s steel booms had been removed to give her a smaller radar signature and more deck space. The Santa Maria was loaded to the gunwales with bales of marijuana, the Guatemalans were armed to the teeth, and the night skies were full of cops.

Teach did the job he had done as kid. He ran out in a twenty-one-foot Boston Whaler, met the Santa Maria and the three surly Latino gangsters, brought the shrimper in, weaving her through a maze of mangrove canals to the place in the Steinhatchee game preserve where Naylor met them with a rented truck. Teach and Naylor off-loaded the bales while the three pistoleros stood around smoking caporal cigarettes and stroking their mustaches. Once, Teach said to the ranking Guatemalan, “Hey, Esteban, why don’t you guys help us with the heavy work here? We get t

his done sooner, you get out quicker. It’s better for everybody.” Teach looked up at the sky, reminding Esteban of the DEA aircraft that patrolled this coast.

Esteban looked at Teach the way he would at a guy who’d just asked for spare change. “Soy soldado. No soy peón.”

Teach knew enough Spanish to get the drift. A soldier, not a laborer. “Yeah, well, we get caught here you’ll be somebody’s pom-pom girl up at Raiford. They like the little brown ones up there.” Teach squared himself, wiped the sweat from his eyes with his shirt sleeve, waited to see what Esteban would do. Maybe he had gone too far this time. He didn’t like the guy, didn’t care for any of the Guatemalans. They were Indians who had worn gaudy suits only long enough to learn how to sneer. Their eyes said they would kill without remorse, and their hands always hovered near the weapons they carried in shoulder rigs or in their waistbands.

Esteban opened his coat and showed Teach the gleaming stainless steel nine-millimeter automatic pistol. He smiled and showed some smoke-stained teeth. His eyes were not touched by the smile. He said, “Quickly, quickly,” pointing a manicured finger at the work still to be done.

Teach did the work, took the cut Blood Naylor gave him, and buried his money deep in the woods. He knew enough about bank examiners, Internal Revenue Service inspectors, and human curiosity to realize that he’d better keep living on a bartender’s wage until he had saved enough to leave town. He’d figure out later what a man did with half a million dollars in cash, a man who did not have paycheck stubs or Aunt Lizzie’s last will and testament to show for it.

Going in, Teach and Naylor had agreed on two things. One: they would do only as many trips as it took to get each of them started in something legitimate. Two: the day either man decided to quit, they were both out of the business.

Blood Naylor took care of distribution in the university city. He knew the black community there, where the white kids went to buy. He promised Teach that no one in Gainesville would ever hear Teach’s name. Teach told himself that he was just a pilot, a man who operated a boat for a couple of hours, a man who carried some harmless agricultural product to a waiting truck. When his conscience came calling late at night before he fell asleep, he called himself a maritime consultant. When he was awake, he called himself a bartender.

The day Teach had the money he needed to start a new life, he told Naylor the next trip would be his last.

They were sitting in Teach’s locked-up, darkened barroom after midnight, drinking Tequila Sunrises and watching the cleanup crew mop the floors. Naylor drew hard on his cigarette, lighting his dark eyes with a red glow. “Old Esteban ain’t gonna like it.”

Teach thought about it. He didn’t like what he’d seen in Naylor’s eyes when the cigarette made them visible. He said, “Old Esteban can find two new humps. We’re sticking to our deal, all right?”

Naylor raised the glass of fruit and alcohol. The next drag on the cigarette confirmed what Teach had seen. Greed.

“A deal’s a deal,” Naylor said. “But what if old Esteban decides he like the two humps he got? Wants to keep them. What we do then?” Naylor put out the cigarette in the sunrise.

Teach wanted to say, That’s up to you, my friend. You made the deal with Old Esteban. You promised me I’d be the ship-to-shore connection, tote a few bales, and that was all. But Teach didn’t say it. Instead: “I got what I want out of this. Next trip’s our last. Cool?”

“Cool . . . cool,” Naylor said. Teach was glad he could not see the man’s eyes now. The voice, the regret in it, was bad enough.

* * *

Naylor came by the bar, middle of the noon rush. He drank a beer, paid for it, and wrote the loran coordinates on a bar napkin. At midnight, Teach took the Boston Whaler from a rented slip behind the house of an old woman who had known his parents. She was eighty, nearly blind, and had no idea when Teach came and went. It was late September, still hot, and there was a bright harvest moon in the sky. Teach wove the Whaler through the maze of canals with high green mangrove walls, following the pathways he had memorized from boyhood fishing in a handmade plywood boat with a three-horse kicker. He smelled the open Gulf before he saw it, punching the Whaler out through a little delta of white sand and driftwood into a low line of breakers.

The moon was high and Teach could see for miles. Off to his right, a low, scudding banner of clouds drifted south on a fresh ten-knot breeze. Teach hoped the clouds would swell and obscure the moon before he made the rendezvous point. He doubted it. Ahead of him, the sky was high and starry, and he could see the silver contrail of an airliner heading for Tallahassee. The DEA Cessna Skymasters flew without running lights, and Teach had little hope of spotting one silhouetted against the heavens before it saw him. He ran without lights too, but it wasn’t much of a precaution. Anyone up there would see his wake, a mile of silver ribbon tacked to his stern.

Well, the Whaler was full of the usual fishing equipment, a lunch, a cooler of beer, and a thermos of coffee. The live bait well was stocked with shrimp, and Teach had even taken the precaution of buying some ballyhoo. If a Coast Guard or a DEA boat stopped him, he’d look like the real thing. But all of this, Teach reflected standing at the Whaler’s steering station with the wind throwing his hair straight back behind him, was little protection. His best safeguard was the enormity of the Gulf of Mexico.

Twenty miles out, he saw the huge bulk of the mother ship rise like a black moon out of the horizon. Six miles away and she had seen him. Her bow doors slowly opened and she gave birth to the shrimper Santa Maria, a dark blot on the shimmering sea. If the timing was right, Teach would arrive just as the Santa Maria was powered up by Carlos, the best of the three gangsters. Carlos, Teach had learned from scraps of stray talk, had been a fisherman before he had taken up the drug trade. He understood and loved boats. Teach cut his speed, and the twin Yamahas complained a little, then settled into a five-knot idle.

He made the bow of the Santa Maria just as the mother ship started her slow, ponderous arc west to deeper water. She would steam a wide five-hour circle and meet the shrimper when she returned, deadheading. Teach tossed a line to Julio and scrambled over the shrimper’s transom.

For the next five hours, the night would belong to Teach and Naylor. Teach had once asked Esteban why the Guatemalans didn’t just let Teach and Naylor take the shrimper in, bring her back out. Why they risked going ashore, three armed illegal aliens. Esteban blew a big huff, gave Teach those el stupido eyes. “What if you jus take de boat? Never return? What about dat?” Esteban struggled with English but had no trouble with his sneer.

Teach had smiled, shrugged. “Hey, we’re all businessmen. We honor our commitments.” Again, Esteban had opened his coat, letting Teach see the big pistol.

The trip was fast and lucky. The banner of wispy clouds filled up with moisture, became a thick dark curtain, and covered the moon. Steering by the loran, Teach found the mouth of the tidal canal and eased the shrimper through a hole in the mangroves with only three feet of clearance on either side. From a hundred yards offshore, no one would even see the hole. From twenty yards off, no one would think the passage was more than three feet deep. But Teach knew a strong current flowed here from a spring not far inland, sweeping the hole deep enough for the Santa Maria.

From this point on, it was slow and careful going. Sometimes Teach had to cut the power so much that he almost lost steerageway. The thick green mangrove walls of the canal lashed the shrimper’s rails. Leaves and torn branches rained on deck. Roosting anhingas and herons cried in the night as the boat ghosted past, her engine thumping. When Teach could take his eyes from his work, he watched Carlos and Julio moving around on deck, kicking branches and debris overboard. Sometimes the sides of the shrimper scraped the great, spidery mangrove roots, painting the boat with streaks of mud.

A half-mile inland, the canal widened and Teach breathed easier, loosening his grip on the wheel. On the foredeck, Julio and Carlos relaxed, lit cigarettes. Esteban stood in the bow like t

he captain he was, staring ahead into the darkness.

Teach reached down and turned on the radio, a rock station from Gainesville. The Stones singing their hearts out: all these years and still no satisfaction. The wheelhouse door opened, and Carlos’s flat peasant face emerged from the darkness. Teach switched off the radio.

“No, no,” said Carlos, smiling. “Déjala encendida. Let it go. Play it.”

Teach turned the music back up. Carlos lit a cigarette, filling the little wheelhouse with the heavy stink of caporal tobacco. He shrugged, offered the gold cigarette case to Teach, who shook his head. “No fumo.” Teach thinking, This little Indian with a big gun wants to be my friend. Well, we’ve been through a lot together.

Teach reached into his hip pocket, pulled out a half pint of Wild Turkey. He took a swallow and offered it. Carlos took the bottle and sniffed it, then drank. Again. “Muy bueno,” he said. “Gracias, amigo.”

Teach nodded, took another bite, and put the bottle away. He saw something, some glimmer through the trees ahead. He caught a murmur of surprised talk from the deck below. Carlos slipped out of the wheelhouse, his feet rapping on the ladder. The Santa Maria was approaching a bend in the canal, and now Teach made out the glow of a lantern, a small boat, a man in it, glittering through the mangrove branches. They had never met anyone back here, though Teach had always known it was possible. He also knew that the only people a man would meet back here at midnight would be locals who observed the unspoken rules of silence.

Teach put the shrimper into reverse and spun her screw until she barely drifted. He went down onto the foredeck. The man in the boat was Frank Deeks. Deeks was a sometime handyman, sometime fisherman, and full-time drunk. Deeks kept his back to the men in the boat as it drifted up, pushing a heavy wave ahead of it, and Teach could see why. Deeks was poaching stone crab traps.

Teach had heard rumors about Deeks doing it. Few men would have dared. A crabber was justified, at least by local standards, in shooting anyone he caught messing with his traps. Looking down into Deeks’s leaky skiff, Teach could see next to the hissing Coleman lantern a bottle of Heaven Hill bourbon and some sandwiches wrapped in wax paper. Deeks wasn’t brave tonight, he was just more than normally drunk.

Suitcase City

Suitcase City